Hawaii’s Fresh Water Future: the essence of life

Any sustainability conversation must include water, and all of its forms and uses. Taking this vital resource for granted has serious consequences for the future of Hawaii and its livability. As Dr. Richard Bennett explains, “…water is the essence of life and the media upon which our world and communities are entirely dependent.”

With a focus on Hawaii Island, the authors sum things up this way… “Hawaiʻi Island has a long history of drought episodes. We have dealt with these short-term events with various site-specific mitigations, however, any changes in how water is managed, allocated, and used, remain elusive and are often controversial.“

BeyondKona is pleased to present Richard H. Bennett Ph.D. and Rhiannon R. Tereari‘i Chandler-‘Īao, Esq. of Waiwai Ola ʻOhana, and their analysis of all things water for Hawaii…

Adding to the County of Hawaii’s Sustainability Conversation: Water, Law, and Policy

This paper advocates for a comprehensive approach to water use policy for Hawai‘i Island.

Water resource and use policies are scattered among several county departments and agencies without requiring the policies to be congruent or coordinated.

When we discuss sustainability, we look out into our future and ask what must be sustained if the natural world, our lives, and our economy will thrive without significant external inputs of money, energy, and resources.

Any sustainability conversation must include water and all of its forms and uses. Water is the essence of life and the media upon which our world and communities are entirely dependent.

This article is a conversation starter for a more comprehensive policy discussion of our water resources, no matter the source.

Changing Climate: There is an international scientific consensus that our climate is changing rapidly. The changes are attributed to human activities that have added insulating gases to the earthʻs atmosphere. How this change will impact specific locations is a matter of considerable scientific uncertainty. However, the recent historical record for Hawai‘i portends significant rainfall declines coincident with sea-level rise.

Many authors stress the issue of water resource sustainability, notably: “Given that approximately 70% of the annual rainfall happens during the wet season, Hawaiʻi is expected to face an overall reduction in annual rainfall leading to a decline in sustainability of groundwater recharge” (Burnett and Wada, 2014).

Rainfall for the state has declined about 14% overall.

Confounding this observation are drier and wetter trends for specific communities on all islands. Hawai’i Island’s leeward or Kona side appears to be drier than any statewide trend may suggest. Wisdom and prudence declare that we must assume the worst-case scenario and plan accordingly. We will be pleasantly surprised should heavier rainfall occur from year to year. In contrast, being shocked and unprepared when protracted drought occurs might inspire emergency restrictions that serve only as band-aids.

Fresh Water: Our water reservoir is a finite underground bubble that floats on the more dense seawater saturating the fractured rock beneath the island. This bubble or lens is rainfall and dew dependent. There is no underground river of fresh water that flows underground, as occurs in some states and aquifers of the mainland.

Our rainfall dependency is also confounded by the time of a rain event until that water joins the lens. Unlike a lake reservoir, this latency of the water volume can make effective water use planning difficult and provide an illusion of water abundance. This raises the question of how best to determine the sustainable yield and limits of our water resource.

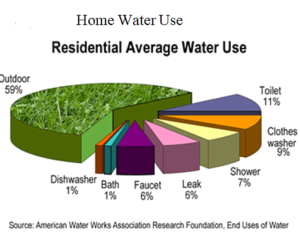

Home Water Use: There are many options for reducing in-home water use. Most of these are structural, such as low flow fixtures and appliances.

The most significant use of water in the home is landscape irrigation. Plant species selection and effective irrigation management can save 30-50% of the water used outside the home. The Board of Water Supply for the City and County of Honolulu states that with the proper choices, a homeowner can save 30 to 50% of the water used on landscaping (2021 Board of Water Supply, City and County of Honolulu). This option conserves water, reduces the family water bill, and addresses multiple crucial sustainability issues.

Irrigation water conservation programs must be an essential component of any sustainability effort for Hawaii. Water conserved for other domestic demands will be far less expensive than increasing pumping capacity, and the energy to drive that capacity, for additional water.

Redirecting the best quality wastewater from sinks, showers, and washing machines can replace 30 to 40% of the water needs for landscaping. Many nations and communities in the arid parts of the world reuse water by necessity and mandate.

Redirecting the best quality wastewater from sinks, showers, and washing machines can replace 30 to 40% of the water needs for landscaping. Many nations and communities in the arid parts of the world reuse water by necessity and mandate.

The challenge for Hawaii County is how best to achieve sustainable policies and water conservation education. The Department of Water Supply is not noted for progressive water conservation policies or effective public education. A change in policy and programmatic efforts will likely require enlightened leadership and engagement from the Mayor Roth and the County Council to effect significant water conservation measures. However, the most significant impediments to greywater reuse are state and local regulations that are onerous, out-of-date and not science-based, and, in some cases, make greywater reuse illegal.

Wastewater Reuse: Hawai‘i Island has several wastewater treatment plants. Some are public; most are private. By statute, our communities may have a typical sewer system into which all wastewater is combined. Toilet water is mixed with sink, shower, and laundry water, and as such, it all becomes “Black Water.” This water must be treated to reduce its pollutant loads and disinfected to reduce the prevalence of presumptive disease-causing microbes. This treatment process is expensive to construct and operate. The proper disposal of the treated wastewater is costly and especially problematic for an island in which sewer connections are more the exception than the norm.

Water inexorably flows downhill to the sea. On the Hilo side, about 212 rivers and streams flow continuously, allowing people to see the hydrologic cycle in action. The Wailuku River in Hilo is a dramatic example. Its watershed is a vast mountainside. Heavy rains create a torrent of brown water carrying dirt and fine sediments into Hilo Bay. Less apparent are the urban drainages of the Waiākea and Wailoa rivers. A drive through Hilo town reveals many storm drains and gutters that convey street rain runoff to these rivers and the bay.

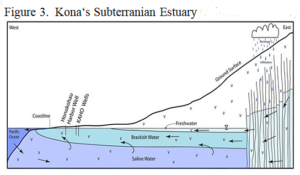

In figure 3, Kona’s Subterranean Estuary is depicted as a model of the water flowing from land-to-sea.

There is only one storm water channel in the Kona area that drains Holualoa mauka. Most rainfall runoff migrates underground and joins the subterranean estuary that flows under the entire Kona plain.

University of Hawaiʻi hydrologists suggest the brackish ground water flows into the sea at the rate of about 2.5 million gallons per mile of coastline, per day (Peterson 2009).

As apparent in this illustration, all water eventually flows into the sea. In some cases by design, and others by default, as is the case with Hawaii Island’s wastewater plant injection wells. In both situations, the law requires all such disposal to be subject to disposal permit requirements to ensure that the nearshore waters are not impaired.

The wastewater of the Kealakehe Wastewater Treatment Plant is a glaring example of water resource mismanagement and nearshore pollution. For over 20 years about 1.8 million gallons a day of partially treated wastewater is dumped in a pit 0.7 of a mile from Honokohau Harbor. At least ten scientific studies document how this water flows seaward, in our subterranean estuary, polluting the harbor and the ocean. A plan that was funded by the EPA in 1993 required the reuse of the water for irrigation.

The wastewater of the Kealakehe Wastewater Treatment Plant is a glaring example of water resource mismanagement and nearshore pollution. For over 20 years about 1.8 million gallons a day of partially treated wastewater is dumped in a pit 0.7 of a mile from Honokohau Harbor. At least ten scientific studies document how this water flows seaward, in our subterranean estuary, polluting the harbor and the ocean. A plan that was funded by the EPA in 1993 required the reuse of the water for irrigation.

Over 20+ years, 13 billion gallons of wastewater were indirectly dumped into the sea while government agencies looked the other way. The water could be used today to irrigate the recreation areas at the Old Airport. Our limited freshwater is used instead in what is nothing more than multi-agency myopia.

Water Policy: The sustainability of our water resources is the kingpin for just about every other sustainability issue. The County of Hawaii and the DWS (water department) must coalesce to implement a whole range of sustainable water policies and practices. Without ample high-quality water for all, at affordable prices, sustainability becomes moot. It is time to become proactive, pick the can up and fix these problems, rather than continue to kick the can down the road of climate resiliency.

In aggregate, storm water runoff and cesspool leachate are the most significant pollutant loads that impair the coastal ecosystem. We must also redesign our communities to manage these waters effectively. Thinking outside the box is not enough. The box itself must be redesigned.

Public Trust: Article XI, section 1 of Hawai‘i’s Constitution establishes that “all public natural resources are held in trust by the State for the benefit of the people,” and Article XI, section 7 of Hawai‘i’s Constitution specifically references water and includes the directive “to protect, control, and regulate the use of Hawai‘i’s water resources for the benefit of its people.” Article XI, section 7 also establishes the State Commission on Water Resource Management (Water Commission), which is currently housed within the Department of Land and Natural Resources. As provided in our State Constitution, all of the state’s resources shall be managed in the “Public Trust.”

Today, “the people of [Hawaii] have elevated the public trust doctrine to the level of a constitutional mandate.”[1] Pursuant to the Constitution, Water Code, and common law, the “state water resources trust” applies to “all water resources without exception or distinction.

[1] Waiāhole I, 94 Hawai‘i 97, 131, 9 P.3d 409, 443 (2000).

The counties and the legislature have largely ignored this doctrine while enacting its business. Embracing this “Trust” will carry us effectively toward a sustainable future.

Sustainability means designing the future from the future, and nothing is more important than water. This is the place to begin.

None of this is ‘wrong’, but frittering about the edges with low flow toilets for instance is a weak but and mildly tolerable social solution for the unimaginative leaps that we really need. End the flush toilet!

No indigenous society would think it wise to defecate in your drinking water supplies.

And finally, I must be said that no discussion of a ‘lack’ of any fundamentally life giving resource should be taken seriously that fails to bring in the balancing subject of ‘overpopulation’ (contextually locally and globally writ large) and its myriad demands thereof .

Thank you for this article on the sustainability of fresh water.

A recent ThinkTech Hawaii video has excellent information from the Hawaii Groundwater and Geothermal Research Center. It shows that some of our earlier thinking about the “freshwater lens” is far from complete or accurate. Funding is needed for more test drilling to more accurately understand Hawaii geology and underground water resources and temperature gradients.

ThinkTech Hawaii https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NI5LPj2_pdM

Hawaii Groundwater & Geothermal Research Center https://www.higp.hawaii.edu/hggrc/