“This (Lālāmilo Wind Farm) is arguably the first time in Hawai’i, and perhaps the nation, that a local government has developed such a wind-powered, water-pumping facility capable of significant greenhouse gas reductions at no-cost to the taxpayer” – United States Conference of Mayors’ Climate Protection Awards – Honorable Mention

Lālāmilo is a wind and water system that works with complete synchronicity delivering customer savings while improving the environment for our island. The Lālāmilo and DWS wind-water system is responsible for moving water to household customers, ranches and the large resorts and provides power to eight (8) deep wells managed by Hawaii Island’s Department of Water Supply, and that represent approximately 25% of the $20 million the department’s energy bill essential to its water system.

The history of the Lālāmilo Wind Farm goes back to the mid-1980s, where the original Lālāmilo Wind Farm developers knew enough about the wind resource in Hawai`i and the Lālāmilo water site that they proposed and eventually developed a wind farm using 1980 technology Jacobs Wind turbines that would both power water pumping operations and when available, provide excess energy to the local electric utility, Hawai`i Electric Light (HELCO).

That original wind farm worked well for a period of time and HELCO’s holding company Hawaiian Electric Industries purchased the wind farm around the year 2000 and included it in HELCO’s renewable energy percentages numbers for the next decade.

The consistent and sometimes destructive wind at the Lālāmilo site eventually destroyed many of the 120 plywood wind turbines and twisted the metal tower structures supporting those turbines into steel pretzels. Combined with a lack of maintenance and spare parts, the wind farm degraded to a point where it was not producing significant energy.

Just before the wind farm was set to be decommissioned in 2010, HELCO proposed re-powering the wind farm with approximately $10 million using more modern and efficient renewable energy technologies, but the parent company was not interested in a wind farm that would be third in line with two other ones already operational and in priority order of dispatch, namely the Hawi (Upolu Point) and Tawhiri (South Point) wind farms.

When I invited National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), a Department of Energy Lab focused solely on Renewable Energy, to the Lālāmilo site in 2009 they were astounded that a relic of early renewable energy systems remained. The wind was blowing steady, as two NREL engineers walked around the historical site in awe.

With stormy skies as the backdrop and only a few turbines spinning with twisted metal towers and plywood blade shards lying about, they took many dramatic pictures determined to bring back home to enchant their fellow engineers. More remarkable to the experienced engineers was that the largest island water pumping system sat under this world-class wind resource.

The Lālāmilo water system responsible for moving water to household customers, ranches and the large resorts comprise eight (8) deep wells that consume approximately 25% of the $20 million Water Department energy bill. NREL engineers then reported back headquarters at Golden, Colorado, easily convincing their colleagues and superiors of the potential to re-power this unique site.

With NREL’s support, I worked diligently with the help of the Water Department’s energy analyst to form an alliance that could successfully lobby to receive Federal grant money from the 2008 Hawaii Clean Energy Initiative for assistance with many technical aspects of the project.

Most of these Federal dollars were used for the rigorous analysis of the wind’s capability to pump water from the eight (8) deep water wells at the Lalalmilo site.

We were also able to get additional Federal dollars to employ a top law firm in Hawai`i to write the legally-binding and highly-technical document that would become the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA). With some insightful modifications from County’s Corporation Counsel, the PPA spelled out the legal terms for the supply and purchase of the wind power.

With the help of NREL visits, we presented to the Water Department – Water Board several times during the period 2010 to 2012; educating them on the wind farm benefits and gaining their full support to go forward with this project. During those presentations, some of the Water Board were shocked that such a well-known and high-caliber Department of Energy – National Lab was interested in them and the Lālāmilo water system.

This was also at a time when HELCO rates had recently been at all-time-highs due to high oil prices and there was tremendous pressure on the Water Department to find solutions to alleviate ever-increasing customer power charges.

The wind farm project all made sense to everyone and the Water Department with the support of the Water Board decided that the re-powering of Lālāmilo was a priority solution to the ultimate goal of saving water ratepayers $1 million per year.

After releasing a Request for Qualifications in 2012, seven (7) bidders sent in their responses to be considered as bidders for the project. As the three-person Evaluation Committee reviewed those qualifications, we whittled those down to three (3) credible developers. The final steps of the process included an initial proposal to the RFP, an in-person (or team) interview along with a Best and Final Offer.

When the interviews were done and final offers reviewed, the unanimous winner was Lālāmilo Wind Company (LWC). LWC had proven they had the experience with their superlative track-record at the Hawi Wind Farm and also that they could provide just what the Water Department needed, namely maximum cost-effective renewable energy that could save their water customers money.

The Evaluation Committee presented their recommendation to the Water Board on April 23, 2013 and the Water Board went into Executive Session for 12 minutes and came out to declare LWC the unanimous winner. To say the least, I was overjoyed that here was a project that would set the new standard for the Water Department and the State of Hawai`i. I had gotten a chance to work with some of the best engineers on the island in the Water Department and we had done the right-thing by selecting the best developer possible.

The PPA was signed in October 2013 and LWC got to work financing and building the wind farm they had agreed to according to the Water Department specifications. Some minor adjustments to the PPA were made that included providing for a Habitat Conservation Permit and Incidental Take Permit, but things were going rather smoothly.

In September 2015, we held a blessing on the Lālāmilo site and as show of approval, the Lālāmilo winds blew gently right on queue and then increased in strength. Public press releases and public speeches rolled from the Water Department announcing the coming of a new wind farm capable of saving the County water ratepayers $1 million per year.

By September 2016, only one year after we broke ground, LWC fulfilled their commitment by producing a modern wind farm capable of handling the extreme wind regime at Lālāmilo and converting that energy in useful electricity for the entire Lālāmilo water system.

For one year starting from September 2016, the wind farm operated in the daytime only as we waited on the results from the Federal approvals and then in September 2017 it went fully-operational. With the new Saddle Road extension complete, most people started to get a regular glimpse of the elegant wind farm as they drive west.

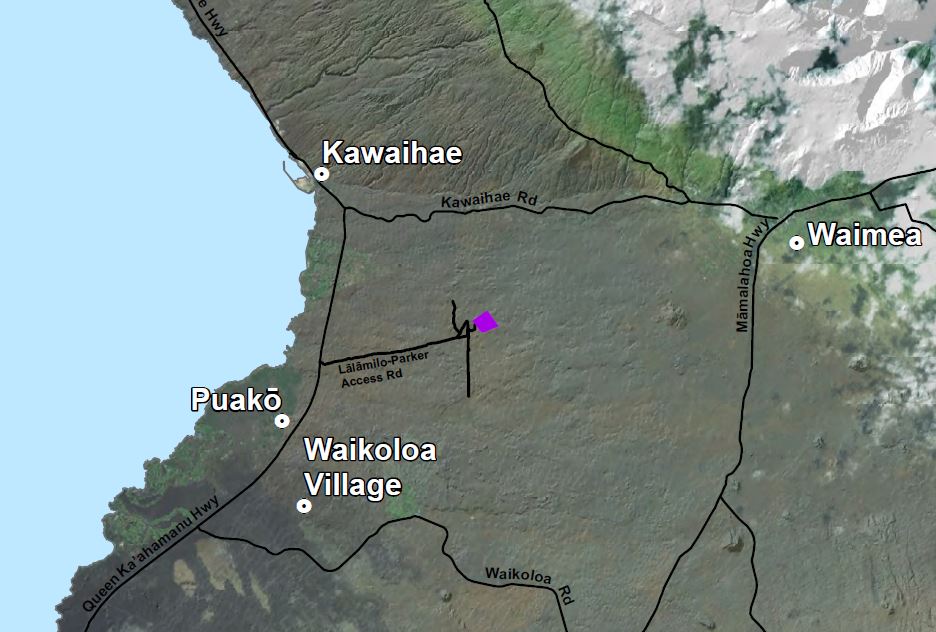

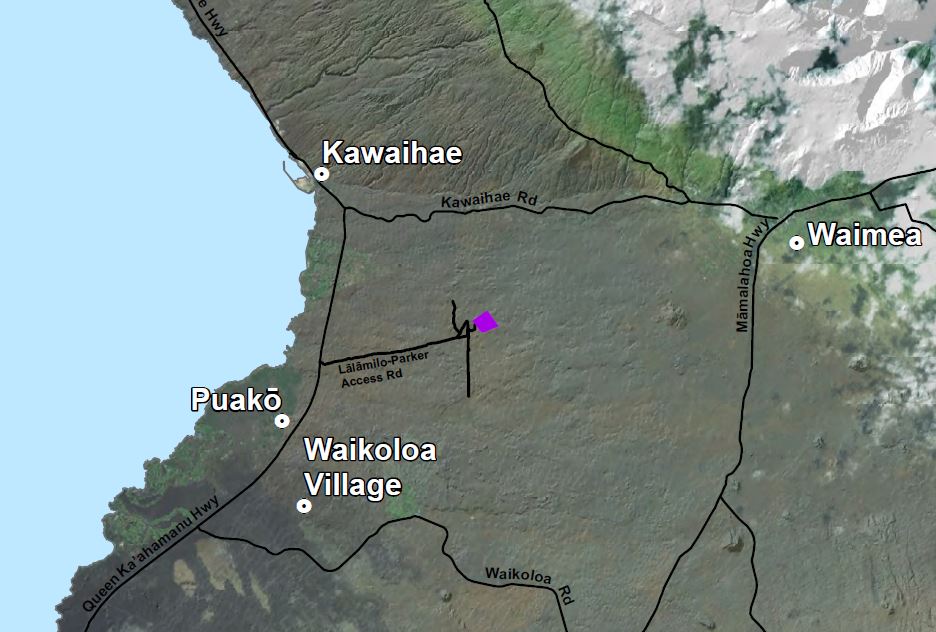

Most folks can see the wind farm as they drive past Waikoloa on the lower road and many see it as the use the upper road to Waimea. As a true testament to LWC’s skill in development and community outreach, there have been no complaints or protests as you see more and more both in Hawai`i and around the world. Recently, in a great wind month like August 2018 that has had consistent wind, you can see all turbines whirring purposefully to pump water.

Unbeknownst to many on this island or the State of Hawai`i, the world was watching our little Big Island as the uniqueness of the Lālāmilo Wind Farm has been in the national spotlight at last year’s United States Conference of Mayors’ Climate Protection Awards.

In the Climate Protection Award category for Large City – Honorable Mention it was written “This is arguably the first time in Hawai’i, and perhaps the nation, that a local government has developed such a wind-powered, water-pumping facility capable of significant greenhouse gas reductions at no-cost to the taxpayer.”

DWS Dispute

Although Lālāmilo Wind Farm is a very significant accomplishment recognized by over 1400 diverse governments including some of the most sophisticated counties & cities, unfortunately, today there is a contractual dispute which prohibits the Lālāmilo Wind Farm from doing what it was designed do.

The main issue at stake is ‘what is the minimum wind energy contracted by the Water Department’. Or from wind farm owner’s point of view, ‘what is the minimum energy that was signed in the contract and relied on to make the project financially viable?’ The Water Department – Water Board has turned the matter over to their lawyers at the County Corporation Counsel.

While this dispute seems to me to be easily resolved, as a former County Energy Coordinator, I have the highest respect for everyone at the Water Department that comprise some of the best engineers I have known since my days working as with top engineers at places like Westinghouse and Siemens. There is every reason for these high-caliber engineers to be proud of a Nationally-recognized wind farm that is part of the most-sophisticated wind-water system in the United States. That means it will take LWC and Water Department working even more collaboratively on continuous quality improvement to match the abundant wind power to the deep water pumps needs and reservoir levels this site.

As an independent consultant, I have made myself available to the Water Department and Water Board in investigating this minimum contact energy issue which was the basis for initiating the project and designing the RFP and PPA from 2009 to 2013.

Today, I am especially encouraged by the persistent efforts of the Water Department as they have recently moved from taking about half of the wind energy provided to now almost two-thirds. I believe by this time next year all the technical and legal issues will be worked out and we will have the very wind farm – water system we envisioned.

Lālāmilo is a wind and water system that works with complete synchronicity delivering customer savings while improving the environment for our island.

As the Water Department mission mandates: “DWS’s mission is to provide affordable water service to the people of Hawai‘i Island. In April 2011, DWS established an energy policy to reduce energy use and its associated costs and environmental impacts. The Lālāmilo windfarm is consistent with this policy and is expected to save DWS customers $1.0 million per year in energy costs over the next 20 years.”

Hawai’i sustainability – past, present, and future

With an ancient legacy of leadership in practical sustainability on a remote archipelago; an ongoing progression of intended results crystalizes when we align vision with performance and continuous learning.

The Lālāmilo Wind Farm was conceived and achieved from this type of vision, performance and efforts from a Water Department and a developer with great minds and hearts. I believe that it is necessary to reclaim the Lālāmilo Wind Farm as a living example of what is possible with the right intentions and the right public-private-partnerships in place. That means that like our ancestors, if we match the best of our great local talent with the great innovation from all over the world, we can continue to create remarkable, world-class achievements.

If we continue to encourage these highly-effective and ethical partnerships to flourish, Lālāmilo and other unique Hawai`i-sourced innovations will continue to provide the foundation of a progression toward actual sustainability.

Over the course of nearly a decade of a public servant career with the County of Hawai`i, the Lalalmilo Wind Farm is by far my highest example on what our Island can do when we come together with vision and courage, no matter what inevitable obstacles we face.

Will Rolson is a contributing editor for BeyondKona.com. He served as County of Hawai`i – Energy Coordinator from July 2009 – April 2018. Will has 33 years’ experience in the energy field as a power engineer, energy analyst and investor. He served the State and County of Hawai`i for the past 11 years, in the capacities of the state’s Renewable Projects Administrator for the Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii Authority, and for Hawai’i County, as the county’s Energy Coordinator.