COP 26: What was accomplished?

In what many consider COP 26 as humanity’s moment for world leaders to correct a dangerous planetary course, national climate pledges are too weak to avoid catastrophic global warming. Most countries are on track to miss them anyway. The global effort to combat climate change boils down to this: Moving forward; or business-as usual and damn the consequences.

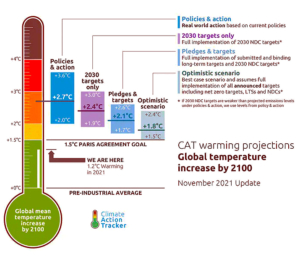

The in-depth study published earlier this week by the Center for International Climate Research (Cicero), concluded temperature outcomes based on countries’ climate pledges were full of uncertainties. Using data on goals set about a year ago, the world now is on a trajectory to warm anywhere between 1.7°C and 3.8°C by 2100 compared with pre-industrial levels. Other analyses that used the most recent data from COP26 came to similar conclusions.

In face of this facts and scientific conclusions, how much did the world accomplish at the Glasgow climate talks – and what happens now? The answer depends in large part on where you live.

In Pacific island nations that are losing their homes to sea level rise, and in other highly vulnerable countries, there were bitter pills to swallow after global commitments to cut emissions fell far short of the goal to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7°F).

Hawaii is far from exempt from climate consequences with the state’s major airports and ports at sea level, both representing the state’s connection to the outside world and its supply chain dependencies.

For large middle-income countries, like India and South Africa, there were signs of progress on investments needed for developing clean energy.

In the developed world, countries still have to internalize, politically, that bills are coming due – both at home and abroad – after decades of delaying action on climate change. The longer the delay, the more difficult the transition will be.

There were also signs of hope as coalitions of companies, governments and civil society and indigenous peoples groups forced progress on issues such as stopping deforestation, cutting methane, ending coal use and boosting zero-emissions vehicles. Now, those promises must be acted upon.

Here are five key elements to watch over the coming year as countries move forward on their promises.

Bending the curve to 1.5°C

Going into the Glasgow summit, countries’ commitments had put the world on a trajectory of warming about 2.9°C this century, well beyond the 1.5°C goal and into levels of warming that will bring dangerous climate impacts. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement in the first days (much to the surprise of Indian observers) that India would reach net zero emissions by 2070 and generate 50% of its energy from renewables by 2030 helped lower that trajectory to 2.4°C.

Going into the Glasgow summit, countries’ commitments had put the world on a trajectory of warming about 2.9°C this century, well beyond the 1.5°C goal and into levels of warming that will bring dangerous climate impacts. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement in the first days (much to the surprise of Indian observers) that India would reach net zero emissions by 2070 and generate 50% of its energy from renewables by 2030 helped lower that trajectory to 2.4°C.

Countries agreed to return for the next round of climate talks in November 2022 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, with stronger commitments to put the world on track for 1.5°C.

U.S. Talking Points

That turns the spotlight back on national action. China reminded everyone, while throwing shade at the U.S., that goals must be backed with plans for implementation. U.S. Cabinet members and Congressional leaders had much to say in Glasgow about being “back,” after the previous administration withdrew from the Paris climate agreement. Yet they had little to offer in terms of the U.S. share of the finance, and the world cast a worried eye over its continued partisan politics.

Deals Done

While all countries are important for reaching the world’s climate goals, some are more important than others.

Countries that are high emitters and heavily dependent on coal will be a focus of international attention in the coming months, not just to phase down coal but importantly to fund a just transition to green sources of energy and the necessary electricity infrastructure.

The poster child for this approach is South Africa, where a presidential commission has worked for three years to develop a just transition plan and has been able to attract US$8.5 billion from the U.K., the EU, the U.S. and others to help them execute on it. That, coupled with guarantees and other financial aid that could help draw further private investment, could become a replicable model.

The key was national ownership. In the year ahead, look for plans to come together in Indonesia and Vietnam and other countries needing to fast forward away from coal.

Follow the Money

In the first week of Glasgow, the titans of the financial industry heralded the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero – the commitment by financial institutions representing $130 trillion in assets to accelerate the transition to a net-zero emissions economy. The shifts within financial markets away from exposure to carbon emissions was palpable. But without more detail, the announcement attracted cries of “greenwashing.”

Throughout Glasgow’s conference halls, officials complained that finance wasn’t flowing to help them succeed.

This isn’t just a climate finance problem. Many countries are also facing economic disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic and have chafed at the way international financial institutions fail to address issues of access to finance and trade. Advanced economies didn’t come to Glasgow ready to provide even the $100 billion a year in finance promised a decade ago, which shrank the landing zone for agreement on all issues.

The Chinese calculate the value of growth lost through a few measures, such as floods and heat. Unsurprisingly it amounts to trillions of dollars. It may be a useful exercise whenever a government balks at the “cost” of climate action.

In the end, governments agreed to reach the $100 billion annual climate finance target within the next two years and agreed that adaptation funding should double. But with the U.N. Environment Program estimating that adaptation funds will need to quadruple by 2030 from today’s $70 billion, there’s a long way to go.

Climate action is a three-legged stool – mitigation, adaptation, loss and damage.

Loss and damage was mentioned an unprecedented 12 times in the final Glasgow texts, but without commitments to funding or mechanisms to secure funding. Loss and damage, or reparations, can be understood this way: you broke it (or endangered it), you pay for it. But, afraid of lawsuits in international courts – which the U.S. does not belong to – or afraid of the costs, developed countries have opposed progress on the issue in recent years.

Developing countries left Glasgow disappointed, but there was no escaping the debate. Although a wonky subject for climate change watchers, future progress is needed towards establishing a global mechanism to help pay for climate-induced losses and damages. With the next year’s U.N. climate conference will be held in Africa, the subject will then likely move to center stage on go-forward agreements between developing and developed countries.

.. recommended additional reading: COP26 — Success or Failure?

Leave a Reply

Join the Community discussion now - your email address will not be published, remains secure and confidential. Mahalo.