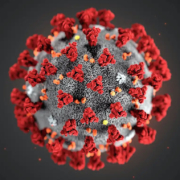

COVID-19; more than a question of life or death

A study of low-risk COVID-19 infected individuals finds impairments four months after first contracting the virus.

Young and previously healthy people with ongoing symptoms of Covid-19 are showing signs of damage to multiple organs four months after the initial infection, UK study suggests.

The findings are a step towards unpicking the physical underpinnings and developing treatments for some of the strange and extensive symptoms experienced by people with “long Covid”, brain fog, breathlessness, and pain are among the most frequently reported effects.

The UK-based Coverscan study assessed the long-term impact of Covid-19 on organ health in around 500 “low-risk” individuals – those who are relatively young and without any major underlying health complaints – with ongoing Covid symptoms, through a combination of MRI scans, blood tests, physical measurements and online questionnaires.

A total of 200 COVID-19 patients in the study had undergone screening suggesting 70% have impairments in one or more organs, including the heart, lungs, liver and pancreas, four months after their initial Covid-19 illness.

There is some post-infection impairment in 25% of the people in the study, affecting two or more organs,” said Amitava Banerjee, a cardiologist and associate professor of clinical data science at University College London.

“This is of interest because we need to know if [the impairments] continue or improve – or if there is a subgroup of people who could get worse.”

COVERSCAN STUDY FINDINGS

Between April and September 2020, 201 individuals (mean age 44 (SD 11.0) 55 years, 70% female, 87% white, 31% healthcare workers) completed assessments following 56 SARS-CoV-2 infection (median 140, IQR 105-160 days after initial symptoms).

The 57 prevalence of pre-existing conditions (obesity: 20%, hypertension: 6%; diabetes: 2%; heart 58 disease: 4%) was low, and only 18% of individuals had been hospitalized with COVID-19. 59 Fatigue (98%), muscle aches (88%), breathlessness (87%), and headaches (83%) were the 60 most frequently reported symptoms.

Ongoing cardiorespiratory (92%) and gastrointestinal 61 (73%) symptoms were common, and 42% of individuals had ten or more symptoms. 62 There was evidence of mild organ impairment in heart (32%), lungs (33%), kidneys (12%), 63 liver (10%), pancreas (17%), and spleen (6%). Single (66%) and multi-organ (25%) 64 impairment was observed, and was significantly associated with risk of prior COVID-19 65 hospitalization.

In some, but not all, cases there was a correlation between people’s symptoms and the site of the organ impairment. For instance, heart or lung impairments correlated with breathlessness, while liver or pancreas impairments were associated with gastrointestinal symptoms.

“It supports the idea that there is an insult at organ level, and potentially multi-organ level, which is detectable, and which could help to explain at least some of the symptoms and the trajectory of the disease,” said Banerjee.

The new findings could also have implications for the management of people with long-term Covid impacts, suggesting the need for closer collaboration between medical specialists. “Sending the people you need to the cardiologist, and then to the gastroenterologist, and then to the neurologist would be an inefficient way to deal with things as the pandemic continues,” Banerjee said.

For Mirabai Nicholson-McKellar, Covid-19 brought an onslaught of symptoms from chest pains to an 11-day migraine, three positive test results, and a period in hospital.

Brain Fog: the long and unclear road to coronavirus recovery

Seven months later, the rollercoaster is far from over: the 36-year-old from Byron Bay, Australia is still experiencing symptoms – including difficulties with thinking that are often described as “brain fog”.

“Brain fog seems like such an inferior description of what is actually going on. It’s completely crippling. I am unable to think clearly enough to [do] anything,” says Nicholson-McKellar, adding that the experience would be better described as cognitive impairment.

The consequences, she says, have been enormous.

“I can’t work more than one to two hours a day and even just leaving the house to get some shopping can be a challenge,” she says. “When I get tired it becomes much worse and sometimes all I can do is lay in bed and watch TV.” Brain fog has made her forgetful to the point that she says she burns pots while cooking.

“It often prevents me from being able to have a coherent conversation or write a text message or email,” she adds. “I feel like a shadow of my former self. I am not living right now, I am simply existing.”

Nicholson-McKellar is far from alone.

Dr Michael Zandi, a consultant at the UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology , says he has seen patients who have been living with brain fog for a few months. While some have been admitted to hospital or intensive care with Covid, Zandi says he is now seeing cases among people who coped with Covid at home.

“The proportion of people with cognitive symptoms for any period of time as a result of Covid-19 is unknown, and a focus of study now, but in some studies could be up to 20%,” he says.

Zandi agrees that difficulties with thinking and concentration have previously been reported by patients with other conditions, including the auto-immune disease lupus.

“Doctors and scientists wouldn’t necessarily use [brain fog] as a diagnosis as it doesn’t exactly tell you what the problem is and what could be causing that,” says Zandi.

Dr Wilfred Van Gorp, former president of the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology, says many Covid survivors he has seen with brain fog also have problems ranging from headaches to difficulties tolerating loud noise and controlling emotions.

“The complaints are very much similar to [those of] post-concussion patients,” he says, adding that there are also similarities to chronic fatigue syndrome.

Zandi says there could be many causes of brain fog in Covid survivors, from inflammation in the body to a lack of oxygen to the brain – the latter is a particular concern for those who spent time on ventilators.

Dr Nick Grey, a consultant clinical psychologist at Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust said terms similar to “brain fog” have previously been used in connection with extreme tiredness, low mood and conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – the latter of which is thought to affect about a quarter of Covid survivors who were in intensive care.

Leave a Reply

Join the Community discussion now - your email address will not be published, remains secure and confidential. Mahalo.