A Climate Experiment Gone Wrong

The world has already heated up by around 1.2C, on average, since the preindustrial era, pushing humanity beyond almost all historical boundaries. Cranking up the temperature of the entire globe this much within little more than a century is, in fact, extraordinary, with the oceans alone absorbing the heat equivalent of five Hiroshima atomic bombs dropping into the water every second.

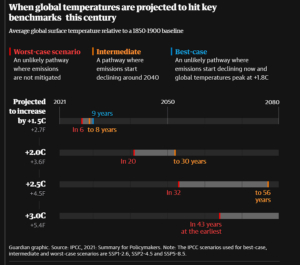

These temperature thresholds will again be the focus of upcoming UN climate talks at the COP26 summit in Scotland as countries variously dawdle or scramble to avert climate catastrophe. But the single digit numbers obscure huge ramifications at stake. “We have built a civilization based on a world that doesn’t exist anymore,” as Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University, puts it.

Until now, human civilization has operated within a narrow, stable band of temperature. Through the burning of fossil fuels, we have now unmoored ourselves from our past, as if we have transplanted ourselves onto another planet. The last time it was hotter than now was at least 125,000 years ago, while the atmosphere has more heat-trapping carbon dioxide in it than any time in the past two million years, perhaps more.

Coral Reefs

One of side effects of this unprecedented planet warming has been the world’s loss of 14 percent of the global coral reef cover, since 2009 — a global network of coral scientists and managers revealed in the first comprehensive update in 13 years on the status of threatened marine ecosystems.

The report, published Tuesday by the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, compiled nearly 2 million observations collected by hundreds of scientists from 12,000 sites around the world. According to the report, following a 1998 bleaching event, coral cover declined by 8 percent, but by 2008, coral had recovered to its pre-1998 levels. In the following decade, however, 4,500 square miles of coral died, or about 14 percent of the world’s coral cover.

“This report confirms what those of us in the coral reef world know to be true, that coral reefs around the world are in big trouble,” said Madhavi Colton, executive director of the Coral Reef Alliance, who was not involved in the report.

The report comes just a few weeks after a research study showed that coral reefs have declined by 50 percent since the 1950s.

The massive decline was largely due to coral bleaching, the report said, which is when warm ocean waters cause the coral to eject the algae it relies on for nutrients. Climate change is warming oceans and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects that 70 to 90 percent of the world’s coral will die if the planet warms 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

The report also found, however, that coral reefs are highly resilient and can quickly recover if conditions change, as they did after the 1998 bleaching event, adding urgency to efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“To me, this report is sounding a loud alarm bell, which is something we should all definitely pay attention to,” Colton said. “It’s a call to action; not all reefs are doomed.”

Other studies show how changes to regional ocean currents and wind patterns also are intensifying extremes. In 2016, researchers found that boundary currents, running parallel to the coast of several continents, are carrying 20 percent more energy than 50 years ago and fueling an increase of destructive flooding in some regions, including Asia, which was highlighted as one of the areas most at risk in the new WMO report.

Too Much and Too Little Water

With global warming intensifying the water cycle, floods and droughts are increasing, the world is unprepared.

The global supply of fresh water is dropping by almost half an inch annually, the World Meteorological Organization warned in a report released this week. By 2050, about 5 billion people will have inadequate access to water at least one month per year, the report said.

Overall, global warming is intensifying the planet’s water cycle, with an increase of 134 percent in flood-related disasters since 2000, while the number and duration of droughts has grown by 29 percent over the same period. Most of the deaths and economic losses from floods are in Asia, while Africa is hardest hit by drought.

“The water is draining out of the tub in some places, while it’s overflowing in others,” said Maxx Dilley, director of the WMO Climate Programme. “We’ve known about this for a long time. When scientists were starting to get a handle on what climate change was going to mean, an acceleration of the hydrological cycle was one of the things that was considered likely.”

Researchers are seeing the changes to the hydrological cycle in its impacts as well as in the data, Dilley said.

“And it’s not just climate,” he said. “Society plays a major role, with population growth and development. At some point these factors are really going to come together in a way that is really damaging. This summer’s extremes were early warnings.”

In the United States, there have been 64 flood and drought disasters since 1980, which cost upwards of $427 billion, or 21.5 percent of the total cost of the country’s climate-related catastrophes compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Globally, the WMO estimates that, between 1970 and 2019, there were 11,072 disasters related to weather, water and other climate-related hazards, resulting in 2.06 million deaths and $3.6 trillion in economic losses. About 70 percent of the deaths associated with climate-related hazards were in the world’s least developed countries.

“There is a long, long history of attempts to improve early warning systems for impacts to agriculture and food security, but the water sector is underserved,” Dilley said. “There are a series of water variables, like groundwater and river discharge, that aren’t being observed.”

Global warming intensifies water-related extremes in several ways. A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, which can fuel more intense rainfall, including from tropical storms. For example, recent research shows that warming will intensify rain from moist streams of air called atmospheric rivers, which already cause most flood damage in the Western United States.

Leave a Reply

Join the Community discussion now - your email address will not be published, remains secure and confidential. Mahalo.