HECO in the Spotlight – Part 1

Hawaii Electric is the state’s 10th largest employer, employing over 2,700. Operating as the states’ only power monopoly Hawaiian Electric companies (HECO) include Hawaiian Electric, Maui Electric and Hawaii Electric Light.

The company is use to getting its way. Under HECO’s power stewardship, Hawaii has the highest residential electricity prices in the United States, averaging more than twice the national average. To put it another way, even though Hawaii residents consume the least electricity in the country we pay the highest electricity bills. On average over the last 10 years, $7,500 more than the rest of the country. (ValueAct Capital 2019 report)

Altogether, HECO islands’ utilities provide electricity to 95% of residents of the State of Hawaii, operating independent and isolated power grids on the islands of Oahu, Maui, Molokai, Lanai, and Hawaii Island. The company claims a customer base of 462,225 commercial and residential customers – impressive with Hawaii’s population of 1.3 million people.

In 2008, the state of Hawai‘i signed a memorandum of understanding with the federal Department of Energy laying the foundation for a 100% renewable energy (electricity) goal to be fully implemented by 2045. HECO was there echoing the then governor’s vision for this historic agreement, “On behalf of the people of

Hawaii, we believe that the future of Hawaii requires that we move decisively and irreversibly away from imported fossil fuel for electricity . . . and towards

indigenously (locally) produced renewable energy…”

Fast forward and a decade later and where is HECO today?

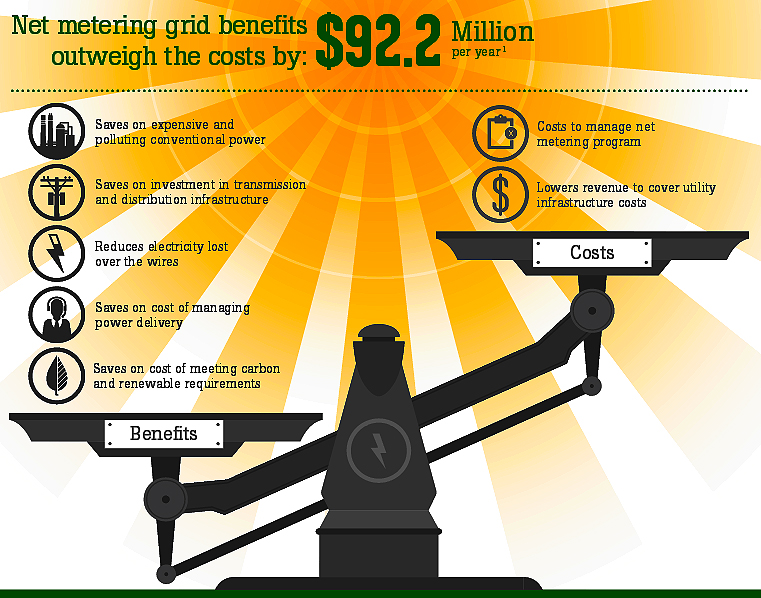

Over the last decade the state has seen a series of clean energy failures from Hawaiian Electric, including its early biofuel-led approach to the renewable energy transformation, the failure of the 400 MW “Big Wind” plan, the failure of ten of the eleven wind and solar projects competitively selected in 2013, the collapse of the rooftop solar industry, in no small part is due to HECO’s lobbying before the state PUC. The objective was simple enough, kill Hawaii’s highly successful NEM (Net Energy Metering) program, the same one that ushered in the state’s transition to a clean energy economy.

economy.

Following a national trend, HECO and other electric utilities wielded their political muscle to reduce and eliminate compensation to customers providing electricity back into the grid. HECO engaged in a analytical paralysis in its effort to develop a response plan to state RPS mandates in the form of a five-year resource planning effort which ended without a firm commitment by HECO and road map for outlining the utility’s clean energy transition.

“…Hawaii continues to enjoy something of an unexamined national reputation as an electricity-policy innovator, but Hawaii has not yet made good on its ambition to lead a clean-energy revolution of global significance.” (National Renewable Energy Lab 2019 report: Hawaii Clean Energy Initiative 2008–2018)

Energy experts – outside the utility wheelhouse – argue that the one-size-fits-all utility performance-based operating model and associated rate schemes now being considered by Hawaii and other PUCs around the country will fail. The struggle with “performance measured” utility operating models is pretty basic: it’s one thing to measure performance, it’s another to develop a compensation formula that fully factors in all contributing parties working together on a path to a 100% clean energy economy.

These same energy experts also argue that utility compensation and rate schemes designed to address a rapidly changing energy marketplace are unlikely to achieved their intended goals. Today’s utility operating model requires greater flexibility, it must be cost effective and accountable, and open to multiple and distributed clean energy generation sources connected to the grid. Equally important, it must include a fair compensation plan for all clean energy contributing parties that power the grid.

The Electricity (Supply) Act of 1926 led to the setting up of the National Grid. So why mess with a working and nearly one hundred year old national power formula which established power monopolies designed to serve as exclusive retailers of electricity operating within exclusive service regions?

As with most historically designed and centralized power generation systems connected by long distance power grids, the core engineering constraint (requirement) are systems designed to match the need of instantaneously electricity demand (“load”) to electricity generation, aka load balancing of power, that is centrally controlled. So long as HECO could operate under historic business and technical models of business-as-usual, and serving as its own exclusive power supplier, all was fine. When you need more money, you have the power and the public needs that power. So you go to the PUC and you generally get what you ask for — rate increases. Its much easier to raise ratepayer dollars than it is to raise venture capital or go to the banks. If you fail or succeed has little consequence to raising more capital through higher customer power rates; operating costs and profits are subsidized by ratepayers.

Rather its shareholders, not utility customers, who are the top priority of privately held utilities with ratepayers subsidizing shareholder dividends – the primary Wall Street measurement of a company’s performance and shareholder value for publicly traded utilities.

Net Metering and Rooftop solar

That all changed when low-cost roof top solar arrived on the energy stage, and utility scale wind, solar, and storage options proved more cost effective than traditional polluting fossil-fueled power stations. For utilities looking backwards, the overall consideration off operating in mode that is much kinder to the environment is generally not a priority, unless they are forced to address head-on their contribution to an emerging global climate crisis as part of their energy equation.

Net Energy Metering (NEM) can be understood as the twenty-first century, distributed power generation system.

NEM gave rise to Hawaii’s rooftop solar industry, which installed more than 500 MW of renewable capacity in Hawaii over the last decade, increasing renewables’ share of total generation by 8 percent. According to HECO, over 60,000 customers have installed solar systems under the successful NEM program within the Hawaiian Electric, Maui Electric, and Hawaii Electric Light service territories.

With NEM, rooftop solar equipment can be sized to produce more (limited to 10 KW) than the customers need during the daytime, generating a bill credit that zeroes out the monthly utility bills (minus HECO’s $25 monthly flat fee for a grid connection).

The capital cost of NEM rooftop solar systems, with a projected life 25 years or more, can be recovered in a few years of operation, with ongoing utility power costs savings costs in what otherwise would have been power consumption costs to meet both day and night electricity demands. For that reason, NEM played a key role in the success of the rooftop solar industry in Hawaii and nationwide, but no more.

Utilities fought NEM from the start, their primary NEM target was the customer power rates that the utility was forced to credit back pay to this new category of utility customer. Within the industry called “prosumers”, but in fact, utilities viewing this special class of customer as … a competitor.

Nationwide in NEM markets, utilities engaged in one-sided and coordinated industry arguments before their governing PUC, and Hawaii was no different. If they couldn’t completely dismantle the NEM program in their market (as was the case Hawaii), their backup strategy was to proposed that rooftop solar owners be only credited for the solar energy provided back to the grid at a credit equal to wholesale power rates. In effect, a instead of fair dollar-for-dollar exchange of power; in which both parties to the NEM program (the utility customer and the utility) each invested in their own power production systems, the utility sells at retail power rates and the customers sells at wholesale power rates back; creating a complete uneven playing field favoring utilities.

In the death of Hawaii’s original NEM program for which HECO argued before the PUC, the utility naturally failed to point out the capital cost investment by utility customers in their rooftop solar systems and the renewable energy cost off-sets benefits to HECO shareholders for this efficient clean power contribution — yielding environmental, social, and regulatory clean-power cost offset benefits to HECO, lowering utility cap-x and fuel costs, and by extension lowering HECO costs to non-NEM utility customers.

Hawaii’s then PUC board bought HECO’s arguments hook, line, and sinker. Ending a program, by any measurement that benefited power consumers, the state’s clean energy transition objectives goals, and contributed to HECO’s meeting its 2045 statewide RPS obligations

After Hawaii’s PUC ended the highly successful “original” NEM rooftop solar program in 2015, a year later the Business Journal reported that the majority of Hawaii solar energy firms reporting significant job losses, once driven to record growth levels in rooftop solar installations across the state.

Today, the collapse of Hawaii’s once robust solar industry has been cut half, losing more than 50% of local (high paying) jobs from the industry’s high water mark in 2012 — mostly, directly attributed to the loss of the state’s original NEM program.

As renewable generation increasingly displaces fossil-fueled generation, the HECO Companies are increasingly planning to supplement this traditional power generation and power delivery formula with batteries, demand response, and dispatchable intermittent renewable facilities.

In the meantime, technology and power consumer options continue to expand, the clean power marketplace continues to surpass HECO’s management timelines for reform, and its heavy resilience on imported dirty energy to fuel its power plant investments or a genuine grid transition to clean energy.

Once considered a far future opportunity for advancing the future of state’s clean energy goals, residential battery storage systems are now beginning to provide Hawaii’s flagging solar industry a needed breath of life. This nascent solar revival now needs reforms in regulations that match customer power storage technology opportunities and options — now readily available to Hawaii’s residents and businesses seeking power security in an uncertain power climate.

The missing piece Hawaii’s promise for clean energy independence is the removal current regulatory barriers to wide scale adoption of solar plus storage – barriers designed by HECO to do just that.

The PUC may discover, with little effort or regulatory wrangling, that enabling distributed storage and distributed solar to be an effective way for to achieve its Hawaii’s 2045 100% renewable energy goals, with HECO full and enabling cooperation. Certainly not the NEM replacement regulations now in effect that establish walls, not bridges to clean energy innovation — and regulations that do not rely in HECO’s permission to proceed with residential and business battery systems that sit behind the utility’s meter.

A coordinated statewide path to clean energy independence

Both the state’s PUC and HECO have yet to realize that rooftop solar plus batteries could also address HECO’s current power management deficiencies with their grid in accepting added solar customers, and re-open the economic benefits of a renewed statewide transition to roof top solar — without delay and unnecessary cost barriers.

Leave a Reply

Join the Community discussion now - your email address will not be published, remains secure and confidential. Mahalo.