What does the Future Hold for Native Hawaiian Lands?

Native Hawaiian land claims and Governor Green’s drive to address affordable housing converge on need, but not implementation

On a one-acre farm at the foot of Maui’s dormant Haleakalā volcano, Kekoa Enomoto grows dragonfruit, pineapples, yuzu, avocado, kabocha squash and chilli peppers. She tends to a laying chicken, two honeybee hives and an aquaponics system that spawns Mexican oregano, lemongrass and tilapia.

Homesteaders like Enomoto live today similar to how Native Hawaiians did for more than a millennium, before Christian missionaries, traders and whalers arrived on the islands in the 19th century. Like other Indigenous peoples in the US, the Kānaka Maoli lived sustainably and took only what they needed from the land, growing kalo and breadfruit to feed entire villages. In the 21st century, it is more an issue for all of Hawaii’s residents (homeless and housed) in reconciling lifestyle and economic means within both changing social and climate conditions.

As a beneficiary of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, a century-old program to return Native Hawaiians to their ancestral lands, Enomoto, 77, pays just $600 a month in mortgage fees for the farm and three-bedroom house where she’s lived for the past two decades. The average monthly mortgage payment in Hawaii exceeds $2,500, the second-highest among all US states. Yet her experience cultivating, raising a family and growing old on land that is her birthright has been far from the norm for Native Hawaiians, who experience the highest rate of homelessness in one of the most expensive places on the planet.

“Kuleana” is Hawaiian for ‘responsibility’, in this case, how best to develop and live on the land. Some will argue today that is what many Hawaiians believe sovereignty is all about, and what Prince Kuhio envisioned. According to Hawaiian custom, kuleana is also only given to those who demonstrate their readiness and worthiness to handle a responsibility.

Despite accounting for only 20% of the state’s overall population, Native Hawaiians make up 50% of the unhoused population.

In 1921, Congress passed the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, which placed 200,000 acres of land that belonged to the Hawaiian Kingdom into a trust. Anyone 18 years or older with at least 50% Native Hawaiian lineage would be eligible to obtain a 99-year land lease for $1 a year. (The leases, which are still available, can be extended by another 100 years.)

In 1921, Congress passed the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, which placed 200,000 acres of land that belonged to the Hawaiian Kingdom into a trust. Anyone 18 years or older with at least 50% Native Hawaiian lineage would be eligible to obtain a 99-year land lease for $1 a year. (The leases, which are still available, can be extended by another 100 years.)

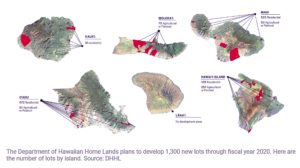

The department of Hawaiian home lands (DHHL), the state agency charged with distributing homesteads, has awarded lots to 10,000 beneficiaries. But nearly 29,000 people remain on the waitlist. In October, the state finalized a $328m settlement agreement with 2,500 waitlisted beneficiaries who had brought a class-action lawsuit against DHHL for mismanaging the public lands trust.

Since its inception, the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act has been riddled with problems. The trust lands had been leased to sugar plantations, and only a limited portion were suitable for residential or agricultural use. A quarter of the allotted acres, in fact, were barren lava fields with limited water access that “a goat couldn’t live on”, the territorial representative William Jarrett said in 1921.

Vast portions of homestead lands also have been developed for purposes other than homesteading. For decades, public agencies have leased thousands of acres of trust lands, for little or even no compensation, to develop schools, parks, airports, military bases and other facilities.

In 1995, the state legislature passed a reparations bill, Act 14, that authorized land exchanges and $600m to settle public use controversies. But the department has continued to invest in commercial leasing projects with non-Hawaiian entities to make up for revenue shortfalls, including a stalled plan to build a casino resort in Oahu.

Another problem, experts say, is that the program has veered away from its goal of affordable home ownership. Residential homestead awards take several forms, including rent-to-own properties and vacant lots on which families can build their own homes. But the most sought-after option among homesteaders is buying prebuilt single-family homes on trust lands. While these turnkey houses cost about half the price of comparable homes elsewhere on the islands, they’re still prohibitively expensive for working-class families.

Another problem, experts say, is that the program has veered away from its goal of affordable home ownership. Residential homestead awards take several forms, including rent-to-own properties and vacant lots on which families can build their own homes. But the most sought-after option among homesteaders is buying prebuilt single-family homes on trust lands. While these turnkey houses cost about half the price of comparable homes elsewhere on the islands, they’re still prohibitively expensive for working-class families.

A 2014 DHHL study found that only 25% of waitlisted beneficiaries said they could afford the 10% down payment on a mortgage for a $150,000 property. As a result, many beneficiaries who were called off the waitlist ended up turning down home-ownership opportunities.

In Maui, there are roughly 1,400 homesteads and more than 3,800 applicants on the waitlist, including many people who were displaced by the Lahaina fire. (Locals in say it felt like a miracle that the Leialiʻi homestead community, which is close to the burn zone and houses more than 100 Native Hawaiians, was left mostly unscathed.)

In September, locals presented to DHHL an emergency proposal to build 300 solar-powered homes on a Lahaina homestead community for displaced waitlist beneficiaries. But the department’s response was lukewarm and described as “… officials weren’t accustomed to beneficiary-driven initiatives, they’re a gatekeeper and they’re obstructive.”

Kali Watson, the director of DHHL, told Hawaii Public Radio in October 2023 that the department was working with 1,400 Maui homesteaders to build accessory dwelling units (ADUs) as temporary housing for displaced family members. The department is also developing 230 new homestead lots in west Maui and has approved construction on another homestead project for next April.

Also in 2023, Governor Green signed no less than three Proclamations Relating to Affordable Housing, each designed to benefit most-lower income residents, and each prioritized state-driven affordable housing projects with the goal and intent to create thousands of new low-income and workforce housing throughout the state.

Leave a Reply

Join the Community discussion now - your email address will not be published, remains secure and confidential. Mahalo.